|

Left: "Afternoon at Mission San Luis", by John LaCastro, 1993, cover plate for Bonnie G. McEwan's The Spanish Missions of La Florida, University Press of Florida, 1993. |

|

Left: "Afternoon at Mission San Luis", by John LaCastro, 1993, cover plate for Bonnie G. McEwan's The Spanish Missions of La Florida, University Press of Florida, 1993. |

While Spain's position of preeminence waned on the European continent following the disastrous defeat of its "Invincible Armada" by violent storms and the English navy in 1588, Franciscan missionaries and Spain's colonial officials in Florida were, by the 1630s, energetically establishing a network of missions and military outposts that would by mid-century dot the Atlantic coastal plain from the Carolinas southward and westward past the Apalachicola River on and inland from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Gradually, however, the Spanish were forced to yield to and withdraw before the aggressive colonization efforts of the English. After several dismally failed colonial efforts in Carolina (named in honor of England's King Charles II), the English established a permanent foothold in the region with the founding of Charles Town (later Charleston) in 1670 and from that point rapidly expanded both their demographic distribution and their influence with the region's Native American populations.

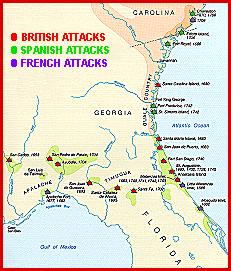

| As

shown in the map at right, greater Florida—with which were once dotted Spanish

missions and outposts from present-day Virginia to the central Florida panhandle

region—was a stage for violent conflict between the English, Spanish, and, to a

lesser extent, the French during the 1670-1740 period. By 1706, the English and their

Indian allies had reduced Spain's once expansive colonial presence in eastern North

America to two tenuously held presidios at St. Augustine and Pensacola. Map adapted from Castillo de San Marcos (Washington, D.C.: Division of Publications, National Park Service, Handbook 149), p. 39 |

|

By 1686, all but a tiny handful of Spain's missions and military posts on the Atlantic seaboard north of San Augustín had been abandoned. After a brief period of uneasy peace between the English and Spanish, renewed hostility pitting England and its allies against Spain and France during the 1701-1713 War of the Spanish Succession (Queen Anne's War in America) afforded the English colonists the opportunity—or so they thought—to rid themselves of their Spanish neighbors once and for all. In 1702 and again in 1704, Carolinians and their Yamassee Indian allies led by James Moore invaded Florida and, while failing to reduce St. Augustine's coquina stone Castillo de San Marcos, they destroyed the city of St. Augustine itself and wiped out the Spanish missions in Florida's panhandle while all but totally depopulating the province of its Apalachee Indian inhabitants and Franciscan missionaries.

The English and their Indian allies also attempted to dislodge the Spanish from Santa María de Galve (the first settlement of Pensacola, established in 1698) in 1707 and again, albeit abortively, in 1711; but, although that town was also destroyed, the settlement was able to defend its wooden fort San Carlos de Austria and ultimately repulse these aggressive efforts. When peace finally came in 1713, only Pensacola and St. Augustine remained to anchor Spain's formerly vast claims in southeastern North America. Meanwhile, the English and the Yamassees, together with the depredating efforts of slavers hunting down the region's hapless Apalachee environs, had put an end to the Spanish mission period in Florida and Guale (Georgia and Carolina) by 1706.

![]()

Spain and other western European nations began to develop uniform dress provisions for their military establishments during and immediately following the tumultuous Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). This process, which evolved over a period of roughly a generation, witnessed western European armies abandoning nearly all but symbolic vestiges of chain mail and armor and adopting uniform clothing styles closely paralleling civilian fashions of the period. By the time the first official regulations for Spanish military uniform dress appeared in 1670, the process of dressing that nation's troops in what would now be considered to be conventional uniform dress had already been ongoing for more than a decade.

Spain's military buckles and buttons of this era resembled those of their French neighbors, albeit with notable differences separating the types. Until the late seventeenth century, most of the buckles utilized were small and quite delicately fashioned, directly descended from forms worn with the protective armor that was fashionable from the earliest years of European exploration and colonization. Indeed, evidence suggests that body armor remained in use among Spain's colonial military population at least to a limited extent until the opening of the eighteenth century. Most military button forms, while exhibiting a variety of shapes and sizes, featured unique shank configurations consisting of looped, cotter-pin-like iron wire eyes integrally cast via the lost wax technique into raised, cylindrical studs on the buttons' reverse faces. These forms dominated until 1700, when a French Bourbon—Phillipe d'Anjou, grandson of French "Sun-King" Louis XIV—ascended the throne of Spain as Felipe (Phillip) V. Thereafter, the often carefully fabricated buckle and button forms of the mid-to-late seventeenth century were rapidly supplanted by more robust (and generally more crudely fashioned) styles in the Spanish armed forces.

While pre-1700 styles of Spanish uniform hardware were being relegated to obsolescence at the beginning of the eighteenth century, they were still in at least limited use by Spain's military establishment in Florida and Guale at the time of the English/Yamassee raids during Queen Anne's War. The illustrations that follow provide a cross section of the typologies utilized by the Spanish troops in Florida and its provincial satellites during the ca. 1650-1700 period.

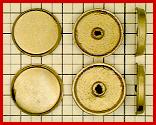

Note: All photographs feature 1/4" gridded backgrounds.

|

|

|

|

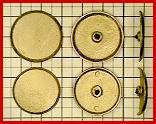

Above: Convex Rimmed Forms

In almost all cases, excavated examples of buttons of this period retain only small lumps of rust where their iron wire eyes were once located. This type of shank was replaced by integrally cast shanks with drilled eyes at the beginning of the 18th century. The most commonly encountered button form of the period was convex with a small outer rim as shown at left, with minority subtypes of this form exhibiting a raised, rounded central protrusion at top and a "bull's eye" obverse design pattern shown at the right.

|

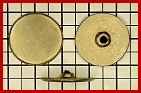

Recessed Buttons Flat, "frying pan" shaped buttons with skirted edges both with and without protruding outer rims as shown at left, right, and bottom comprise other frequently encountered military button subtypes of the ca. 1650-1700 period.

|

|

Ornately Embellished Stud-Shanked Buttons Ornately embellished and occasionally silver plated or gilded cast brass or bronze types like those shown at right are considerably larger and generally more carefully crafted than their more prosaic counterparts. These may have seen use as officers' or gentlemen's cape or cloak buttons rather than as functional coat fasteners of the period. |

|

Formative and Ancestral Button Typologies

Certain stud-shanked button types are virtually identical in fabrication, shape and finishing characteristics to later and more frequently encountered forms with drilled shanks. These stud-shanked buttons may be directly ancestral to their drilled shank counterparts of the eighteenth century and thus may represent formative, prototypical stages of Spanish military button evolution. Several of these hypothetically formative examples are shown below. Later, drilled shank typologies are illustrated and described in the Early Buttons section of this web site.

|

Stud-Shanked Convex Pattern With the exception of its shank configuration, this somewhat irregularly fabricated and slightly convex/concave subtype is virtually identical in construction and form to the later Florida typology, whose members have integrally cast, drilled shanks. This form lacks the outer rim of and is less carefully made than its stud-shanked convex counterparts of the period. |

|

Stud-Shanked Flat Pattern If this form had an integrally cast, drilled shank rather than the stud-mounted iron shank it once mounted, it would be a classic example of the eighteenth century América Spanish military button classification. |

|

|

Stud-Shanked Octagonal Pattern This variety of stud-shanked button may be ancestral to the San Agustín typology of the early 1700s, although it lacks the thickness and deliberate edge beveling of that later classification. Of the hypothetically formative examples shown, this button deviates the most from its possible successor. |

Small Strap Buckles Small strap buckles of this period tended to be small and carefully crafted as shown in the illustration at right. The examples shown, all of which can be nominally considered to be military in use, were probably worn on and with body armor and are often virtually indiscernible from forms utilized as much as a century earlier. These are very similar to other European small strap buckle types of the late sixteenth through the dawn of the eighteenth centuries, and they exemplify the fact that many styles of European military accessories of this period were very similar to one another. |

|

|

Early Large Strap and Belt Buckle Forms Prior to the advent of regulations or the dictates of military fashion which called for the use of any particular type of buckle or hasp, more ornate buckles than those that would normally be considered as military styles are recovered within military habitation and occupation contexts. An example of such a strap or small belt buckle is shown at left. Though crudely cast, this comparatively ornate form features incised hatch lines along all outer buckle frame surfaces emanating in perpendicular directions from the outer to the inner buckle edges. |

Acknowledgments:

Jim R. Baldwin; Michael Buchanan; Tim Cage; Allen Casey;

Shannon Cripps; Roger Harris; Bill R. Logan; Clifford G. Orth; and Arthur, Imogene, and Samuel Standard