|

Left: Map of Spanish Exploration and Early Colonization Activities in North America, 1513-1607. Source: Henretta, Brownlee, Brody, Ware and Johnson, America's History, Third Edition. (New York: Worth Publishers, 1997, p. 39) |

Beginning with and for nearly a century following the discovery of Florida by Juan Ponce de León in 1513, North America hosted a series of Spanish exploration efforts that met with mixed and occasionally catastrophic results. The 1519-1521 conquest of México by Hernán Cortez's conquistadores and the material profits emanating from the seizure and exploitation of its incredible riches served as an irresistible incentive for subsequent and intensive exploration efforts further north. Though these later Spanish explorers failed to encounter or enrich themselves through the treasures or glory they vainly sought, they did succeed in opening both the southeastern and southwestern regions of that subcontinent to subsequent Hispanic settlement and colonization.

A brief chronological summary of significant North American European exploration and colonization activities during the 1513-1609 period is included here as a basis for reference:

|

DATE: |

EVENT: |

|

1513: |

Discovery and initial documented European coastal exploration of "La Florida" by Juan Ponce de León |

| 1519-1521: | Conquest of Aztec empire in México by Hernán Cortéz |

| 1521: | Hostile Native Americans frustrate Juan Ponce de León's attempt to establish colony in Florida (probably San Carlos Bay area); León wounded by arrow in thigh and withdraws settlers; León dies shortly thereafter in Cuba from infected wound |

| 1520s: | Much of coastal southeastern North America probed and investigated by Spanish slaving expeditions (slavers may have arrived in Florida as early as the first decade of the 1500s) |

| 1526: | Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón establishes first named European settlement in what is now the United States, the short-lived colony of San Miguel de Guadalupe in coastal Georgia (September 29); settlement fails after less than two months |

| 1528: | Pánfilo de Narváez lands near Tampa bay and begins ill-fated exodus from Florida to the Texas coast that will ultimately cost his life and the lives of all but four of the expedition's 300 original members |

| 1528-1536: | Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and three other survivors of ill-fated Narváez expedition dwell among the natives in Texas until 1534 and then walk overland to find their countrymen, ultimately arriving in Mexico City on 24 June 1536 |

| 1533: | Dispatched by Hernán Cortéz, pilot Fortún Jiménez discovers the Baja peninsula and names the region California |

| 1539-1543: | Hernando de Soto lands south of Tampa Bay and begins expedition that will take his force 3,700 miles through Florida, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas; after the loss of half their number and Soto himself, the survivors reach the safety of Río Pánuco in 1543 |

| 1540-1542: | Francisco Vásquez de Coronado leads army of mixed conquistadores, missionaries, Mexican Indian allies and 1,500 pack horses on fruitless venture to find fabled treasure cities of Cibola; in the process he opens pathways for later Spanish enterprises from New Mexico and Arizona to Kansas |

| 1542-1543: | Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo reaches Pacific coast of present-day United States and explores region from southern California to Oregon |

| 1549: | Dominican Fray Luis Cáncer de Barbastro and comrades killed during effort to peacefully befriend Indians in Tampa Bay area of Florida |

| 1559-1561: | Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano founds colony near present-day Pensacola, Florida; after a hurricane devastates settlement and other misadventures frustrate and ultimately doom effort, Spaniards abandon region in 1561 |

| 1562-1564: | Jean Ribault commands French expedition consisting largely of Calvinist Huguenots to Florida; after initial landing at mouth of St. Johns River, settlers sail northward and establish colony and build Charlesfort at Port Royal harbor in present-day South Carolina. Ribault's arrest and detention in England as well as disturbances in France prevent resupply and reinforcement of Port Royal, and disheartened settlers abandon colony by 1564 |

| 1564: | French under command of René Goulaine de Laudonnière return to Florida and establish Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville on St. Johns River, but when supplies run short many colonists mutiny or desert; some of the deserters resort to piracy and are captured by the Spanish, who thus learn of the French intrusion into the heart of their shipping lanes |

| 1565: | Jean Ribault named to replace Laudonnière and leads fleet to reinforce Fort Caroline; meanwhile, acting upon urgent orders from King Philip II of Spain, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés establishes San Agustín (St. Augustine), first permanent European settlement in present-day United States. After failing in attack on new Spanish outpost, Ribault's fleet wrecks along Florida coast in storm and Menéndez's soldiers slaughter both the French garrison at Fort Caroline (renaming it Fort San Mateo thereafter) and many survivors of Ribault's shipwrecked expeditionary force at Matanzas (place of slaughter) Inlet; also capture other members of Ribault's force near the wrecksite of their ship, the Trinité |

| 1566: | Menéndez begins process of exploring much of Atlantic seaboard of modern United States and Canada and establishes colony of Santa Elena on present-day Parris Island, South Carolina to serve as capitol of Florida; Captain Juan Pardo dispatched from Santa Elena on first of two exploratory expeditions into North American interior, where he journeys to the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina and establishes small colony at Cuenca and post of Fort San Juan |

| 1567: | Juan Pardo sets out on second inland expedition, this time reaching eastern Tennessee; fearing Indian aggression, Pardo reverses course and returns to Santa Elena |

| 1568: | French aristocrat and privateer Dominique de Gourgues directs force that destroys Fort San Mateo (formerly Fort Caroline) in revenge for the massacre of Fort Caroline's defenders and members of Ribault's expedition |

| 1570: | After the failure of similar attempts in southern Florida, group of Jesuits led by Father Juan Baptista de Segura establish small mission of Ajacán in Chesapeake Bay (Bahía de Santa Maria) region near later site of English settlement of Jamestown |

| 1571: | Chesapeake Jesuits at Ajacán wiped out by Indians led by Luis de Velasco (A.K.A. Opechancanough, Massatamohtnock), Indian captive trained and educated by Spanish who later escaped to rejoin his people and become nemesis of Europeans settling in region until his death in 1644 at purported age of 100 |

| 1576: | Santa Elena temporarily abandoned as result of incompetent leadership, after death of Menéndez two years earlier, of Hernando de Miranda and threat of imminent Indian attack |

| 1580s: | Franciscan missionaries revisit and establish missions among Native Americans in San Felipe de Nuevo México (New Mexico) among Pueblos in region explored forty years earlier by Coronado |

| 1585: | Sir Walter Raleigh recruits his cousin, Sir Richard Grenville, to lead a group of men to establish English colony on island of Roanoke off coast of North Carolina; colonists quickly antagonize natives in region and run short of supplies |

| 1586: | After sacking Santo Domingo and Cartagena, Sir Francis Drake raids, plunders, and razes town of St. Augustine; Drake also removes surviving, beleaguered English colonists from Roanoke |

| 1587: | Santa Elena destroyed and permanently abandoned by colonists who leave to concentrate in St. Augustine after Drake's raid; Raleigh launches second attempt to establish colony at Roanoke, landing 117 additional settlers at site |

| 1588: | Catastrophic defeat and destruction of half of Spanish "Invincible Armada" during failed attempt to invade England results in shift in European balance of power and beginning of decline in Spain's influence and prestige |

| 1590: | Delayed by events at home that prevent resupply or reinforcement of colony, English relief force returns to Roanoke to find settlement abandoned; members of "lost colony" never seen or heard from again |

| 1598: | Juan de Oñate leads heavily armed force to take possession of New Mexico and to "pacify" the region's native inhabitants; he then proceeds to launch first of three expeditions to locate Pacific Ocean from newly conquered lands |

| 1607: | First permanent English colony established at Jamestown, Virginia |

| 1608: | First permanent French colony in North America established by Samuel de Champlain at Québec on high bluff overlooking northern bank of St. Lawrence River in present-day Canada |

| 1609: | Englishman Henry Hudson explores and names Hudson River while employed by Dutch, establishing basis for later Dutch occupation of New Amsterdam (later New York); Spanish colonists found Santa Fe in New Mexico |

The clothing and equipment utilized by Spain's earliest explorers and settlers were in conformity with trends of attire and armament standards common throughout Europe during the period. During this, the twilight of the age of armor, Spain's soldiers and male colonists were outfitted in a mixture of chain mail, conventional armor, and clothing that reflected European fashion at the time. As time passed, the use of metal armor and mail waned and was often replaced in use by quilted and padded vests and protective body padding inspired by and copied from forms utilized by Native American warriors. Such padded armor was first used by the Spanish in their conquest of the Yucatan and was later employed during the Soto expedition. At length, all but symbolic vestiges of armor disappeared by the mid- to late-seventeenth century as its use on the battlefield was rendered ineffective and obsolete by weapons and tactics that would characterize the Baroque period and the dawn of the eighteenth century.

Fragments of armor, mail, and brigandine have all been recovered from sites utilized by the explorers and early colonists of the New World. Also excavated have been usually small buckles, hasps, and fasteners employed on armor, clothing, straps, accouterments, harnesses and saddlery. Unlike buttons, which evolved through a series of stylistic changes relatively rapidly through time once they made their first appearance, buckles of the period remained largely unchanged in overall appearance and configuration for well over two hundred years. Small strap buckles of the fifteenth through early seventeenth centuries were virtually identical and are most reliably differentiated by the historic contexts in which they are observed or from the archaeological strata from which they are recovered in situ.

One of the most popular and widely worn elements of men's martial and dress attire during the period of the Renaissance through early Baroque periods was the doublet. Many varieties of this versatile garment appeared during the approximately three centuries of its use, but its popularity reached a zenith during the period of Spain's exploration and early colonization of North America. Generally speaking, the doublet was a tight fitting body tunic usually cut longer in the front than in the back. These tunics usually had short, upright collars and were worn with or without sleeves. Occasionally they were fitted with removable sleeves to provide their owners with a sleeved or sleeveless dress option. One of the most popular sixteenth century doublet forms was the "peascod" type, characterized by an accentuated bulge in the lower midsection. Doublets could be worn over chain mail or under armor, or even under another, slightly oversized doublet. Some expensive sets of body armor were made to mimic the cut and contour of the doublets that served as their fabric counterparts.

|

Right:

Spanish Military Dress, Armada Campaign, 1588. The apparel shown in this illustration was typical of Spanish military dress both in Europe and in the New World during the last decades of the sixteenth century. Note the doublets and the peascod doublet-shaped body armor of the ensign. Garments like these would have been worn at the time of the founding of St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 and the Spanish colonial occupation of Santa Elena on modern-day Parris Island, South Carolina during the 1566-1587 period. Source: John Tincey and Richard Hook, The Armada Campaign 1588. (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Osprey Military Elite Series No. 15, 1999, Plate K, p. 43.) |

|

Doublets were fastened in the front via hooks and eyes, cloth tie strips or small straps, cloth covered bone buttons, buttons formed by plain or ornately knotted cords, and more conventional metallic buttons. In archaeological contexts, only the metallic forms survive in appreciable quantities. Characteristically, these doublet buttons were very small. Some were very plain, resembling small caliber pistol balls with shanks attached to them; others were much more ornately fashioned. The great majority were made of solid cast brass or bronze.

It is not clear when metallic buttons first came into use during the period of European exploration and colonization. No metal buttons have been recovered from any North American archaeological or historic context predating the period of the occupation of Fort Caroline by the French and St. Augustine by the Spanish. It is hypothesized that, in Europe and America alike, metal buttons first appeared at some time after ca. 1550. This hypothesis is supported by the absence of such buttons from known sites utilized by members of the Soto, Coronado, or Luna expeditions or from the wreck site of the English ship Mary Rose, which sank in 1545 during the reign of King Henry VIII. It is believed that such buttons are likely to have seen use by members of the 1559-1561 colonial effort by Tristán de Luna in Florida. Cultural materials directly associated with that debacle are at this time limited in quantity and diversity and it is believed that future investigations will probably result in the recovery of such buttons.

Artifacts from

the Ribault Survivors'

Encampment • 1565

Following the massacre of the French garrison at Fort Caroline by Spanish troops under the command of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in 1565, the Spanish turned to the south and dispatched with similar brutality many of the survivors of Jean Ribault's shipwrecked relief force at the Matanzas Inlet south of the newly established colony of San Agustín. A small number of these Frenchmen escaped the slaughter of Matanzas and the subsequent surrender of their comrades near the site of their wrecked ship, the Trinité, the latter of whom were spared the fate of their unfortunate fellow castaways. Instead, this group of about twenty-one individuals refused to surrender to the Spanish and are believed to have elected to hide and live among the local Surruque Indians at and in the immediate vicinity of old Cape Canaveral. Three small campsites located within close proximity to one another were located, investigated by, and named for Douglas R. Armstrong and his associates. These have yielded an assemblage of artifacts strongly believed to have been used by these survivors, including French coins of the 1550-1565 period and the earliest known French buttons and strap buckle thus far recovered in North America.

NOTE: All artifacts are shown on 1/4" gridded backgrounds.

|

|

|

|

|

French Buttons and Strap Buckle, Ribault Relief Expedition of 1565 The buttons and buckle shown above were recovered from a campsite complex near Cape Canaveral, Florida believed to have been occupied by survivors of Jean Ribault's ill-fated French expeditionary and relief force of 1565 (see text above). They are, from left to right: Cast brass doublet button, virtually identical to Santa Elena Solid Cast examples recovered from the site of that capitol of Spanish Florida (1566-1587) and shown later on this page; small cast brass strap buckle, typical of European styles of the period; and a very early openwork false filigree doublet button consisting of cast cuprous alloy, semispherical front and back components brazed or soldered together in clamshell fashion. |

||

Spanish Buttons and Buckles, Ca. 1565-1675

The earliest examples of Spanish buttons recovered from datable contexts in North America have been excavated at sites associated with the founding of St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 and the occupation of Santa Elena on Parris Island, South Carolina. Later forms of small buttons generically referred to as "doublet buttons" were used until the last half of the seventeenth century. By 1675, the doublet had become obsolete as a fashionable element of clothing in Europe, having been replaced by a form of men's jacket or coat called a justacorps.

It is important to note that buttons and buckles of most of the types shown were worn by soldiers and civilians alike. More often than not, particularly in the colonies, civilians and soldiers were one and the same. While some soldiers may have worn uniform-like clothing of the same cut and color as a result of the utilization of stocks of supplies on hand or the mandates of their respective commanders, the term "uniform" must be very sparingly applied until the period following the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). Until that time, uniforms in the conventional sense — which mimicked men's civilian dress patterns of the period — did not come into common use in Europe or America. The first Spanish military uniform regulations did not appear until 1670, although there is evidence that an evolutionary trend toward the development of uniform dress codes for the Spanish military establishment began somewhat earlier.

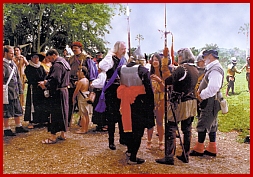

|

Drake's Raid, St. Augustine Reenacting the period of Sir Francis Drake's raid at St. Augustine in 1586, members of this group of living history interpreters wear costumes that represent some of the varieties of military, civilian, religious and Native American attire and weaponry that would have been utilized by the Spanish in North America during the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Programs like this annual event provide the public with a valuable and enlightening insight into the early years of European contact on this continent. |

In the section that follows, all artifacts are illustrated on 1/4" gridded backgrounds. Artifact typologies that have been observed with sufficient frequency to establish a basis for temporal and attribute-based interpretation have been assigned typological classification nomenclatures for reference purposes.

|

|

|

|

Menéndez • Ca. 1565-1566

This solid cast brass doublet button typology, resembling a metallic version of an orate Turkish knot, has been recovered from the site of what is strongly believed to have been the location of the first occupation of St. Augustine by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés' expeditionary forces in 1565. This site is located on the present-day property of the city's Fountain of Youth historic park complex. Other examples of the same typology have been retrieved nearby. All examples are semispherical in cross section, with integrally cast perforated stem shanks. The obverse design consists of a central "eye" surrounded by a design set in four repeating patterns comprised of alternating raised dots lines arranged at perpendicular angles to each other. The majority, but not all, of the observed examples of these buttons bear clearly visible traces of having originally been finished with a gilded surface. No examples of this form have yet been recovered outside the St. Augustine area.

|

Unclassified , Embellished Variant • Ca. 1565-1570 This doublet button form strongly resembles and is probably very closely related to the Menéndez classification shown above. Identical to the aforementioned typology in construction and site-related association, it differs from Menéndez examples only in details of its facial design. The example shown was originally gilded, and, like its related counterpart, it features a central raised, nipple-like protrusion. Emanating from the center outward, however, are alternating raised lines and dots forming abstract cross-hatch patterns set in gently curving spirals extending from the domed facial apex toward a terminus at the button's lateral shoulders. |

Unclassified Glass Button • Ca. 1565-1585 Diminutive and delicately fashioned, this button consists of a cast glass body with an embedded brass wire shank. The glass is semispherical in shape with rounded shoulders and seven indented flutes or grooves cast into its lateral edges. The example shown was recovered from St. Augustine and may have adorned a dress or other element of lady's clothing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

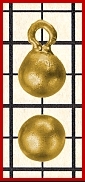

Santa Elena Solid Cast (Spherical) • Ca. 1565-1585

Recovered from the 1566-1587 site of Santa Elena on Parris Island, South Carolina, this solid cast yellow metal alloy doublet button form features a spherical body with an integrally cast, looped shank. Examples vary in quality from exactingly cast and finished (see examples at upper left and lower right) to quite crudely formed. Members of this typology were cast in what appear to have been two-piece molds and then polished to remove obtrusive casting seams and other imperfections. Several, but not all, observed examples of this form were originally gilded. Buttons of this general form and shape saw use until the dawn of the seventeenth century.

|

|

|

|

Santa Elena Solid Cast (Semispherical) • Ca. 1565-1585

This typology is a semispherical version of the solid cast doublet button examples shown above. Fabricated of solid cast brass with integrally cast, circular shank eyes, members of this classification differ in fabrication from their spherical counterparts only in that the majority, rather than the minority, of the examples observed were finished with a gilt coating. While no spherical examples have yet been observed from the St. Augustine area, the example shown at right, above with a residual casting sprue protrusion on its shank was found on Anastasia Island near St. Augustine. It has long been hypothesized that, soon after the initial occupation of San Agustín, the Spanish removed themselves to that island to establish a new fort and settlement site there.

|

San Felipe • Ca. 1565-1585 Named for the Spanish fort at Santa Elena, the construction of this doublet button variety consists of a cast brass spherical body with an embedded, twisted wire shank. Members of this form have also been recovered at St. Augustine, but those examples lack the crossing twist that forms the button's eye. The St. Augustine buttons have more simply formed, cotter pin-like wire shanks. An example of a St. Augustine variant was not available for illustration here at this time. The specimen illustrated here retained a small amount of its original gilt. |

|

Santa Elena Thickened Shank • Ca. 1565-1585 This doublet button variety's attributes include a cast brass, spherical body with a thickened wire shank. The eye appears to have been formed by immersing a bent piece of wire in melted wax and then inserting the end of that now-thickened wire shank into a wax ball that formed the button's body. The entirety of this preform was then subjected to the lost wax casting process, which resulted in the completed button. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of excess metal at the juncture where the button body and shank meet. Examples observed bear no evidence of having been gilded. |

|

|

Casa Fuerte • Ca. 1565-1585 Another of the typologies represented at Santa Elena, the Casa Fuerte button shown is the only one of several examples recovered whose shank is still intact. The typology's cast, spherical body is made from a hard and brittle white metal alloy with an embedded brass wire shank. Several of the examples recovered were broken into pieces, apparently having shattered as the result of the expansion of their shank components as the wire from which they were formed oxidized. Each of the remaining, intact button bodies observed has a clipped and finished sprue removal spot located near the shank (see the overhead view at bottom right). Both the material from which the button's body was made and the presence of the sprue scar as a characteristic attribute of the examples observed set this classification apart from other types of the period. The examples recovered by and in the curatorial custodianship of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology were recovered from what may have been the residence of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés at the Santa Elena site. |

|

|

|

|

|

Small Strap Buckles • Ca. 1550-1600

The cast brass buckle examples shown above were recovered from the Santa Elena site complex and represent a cross section of 16th century Spanish small strap buckle styles. The hinged buckle at center served to secure a strap that connected two matching halves of a set of body armor and was peen-riveted to its host. These examples are very similar to other European forms of the period.

|

Iron Strap Buckle, Ca. 1565-1585 The heavily oxidized iron strap buckle at left was among a number of such artifacts recovered at the site of Santa Elena. While iron and brass buckles and hasps were utilized in roughly equal numbers originally, most iron examples have little or no metallic content remaining when found. |

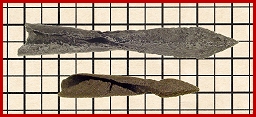

Crossbow Quarrel Points Crossbow dart points like these were used by Spanish colonial soldiers from the time of their first arrival in the New World until as late as the early eighteenth century. Iron points like that shown at the top were made in Europe, while cuprous alloy dart tips like that shown below were fabricated in the New World. The iron projectile point was found near St. Augustine; the copper example was recovered from a site believed to have been visited by members of the 1559-1561 Luna expedition near Pensacola, Florida. Both artifacts have diamond-shaped distal ends. |

|

|

|

|

|

Anastasia • Ca. 1600-1625

Characterized by their very large, circular shanks, members of this classification have been recovered in the St. Augustine vicinity. Made of solid cast brass, examples were either made in two-piece molds and exhibit telltale mold seams (left and right) or were made via the lost wax casting process (center). As the photographs illustrate, these doublet buttons are biconvex in cross section with a variety of similar facial designs consisting of rays or lines emanating outward from a central, hub-like protrusion toward the buttons' outer edges. The specified period of manufacture and use of these buttons is tentatively assigned based on studies of very similar forms excavated in Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Unclassified Pewter Doublet Button • Ca. 1625-1650 Although pewter did not achieve popularity as a button making material until the 1700s, it did see limited use during the preceding century. The button shown here was recovered near St. Augustine and has a very high lead content. Its robust, bullet-like conical body and pedestal mounted shank eye are very similar to examples recovered in Europe that occupy the temporal horizon noted. |

|

|

Faceted and Stippled Doublet Button • Ca. 1650-1675 This very late, cast brass doublet button example features a slightly raised and hexagonally faceted face with stippled embellishments adorning each of its segmented surfaces. The integrally cast, perforated stem shank that this specimen mounts came to be the most common and popular shank form utilized by the Spanish during the eighteenth century. |

|

|

|

|

Rimmed and Domed Forms • Ca. 1650-1700

While the example at left was almost certainly a very late doublet button form, the other two specimens illustrated at center and right, recovered in the St. Augustine area, have more delicately fashioned shanks and may not have been utilized on this element of clothing. By the time that this type of button saw use, doublets were fading into obsolescence as elements of clothing and larger, more conventional button forms were introduced and had achieved virtually universal acceptance and popularity throughout Europe.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks are offered to the following

for their invaluable cooperation and assistance in the completion and

presentation of this section:

Douglas R. Armstrong; Chris Bennett; Brian Bowman; Florida Museum of Natural History; Florida State Museum; Fountain of Youth Historic Park Complex; Richard W. Lanni; Dick Holt; Ed and Marian Hurley; James B. Levy; Clifford Orth; South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology; Warren Tice; Arthur and Imogene Standard; Noel Wells; and Geoffrey Zitver